The first two bars are genuine but for the years 1934 and 1936, and the third bar may be accurate though I’ve not tracked down the source; this was a brief high point. Latvians, a smaller population, were a majority of the early Cheka commissars; why doesn’t anyone care? (Jews and the secret police is dealt with below.) Bar four is fake: Robert Wilton forged his statistics on the payroll of the White Army. Bar five is literal Nazi propaganda and bar six is the testimony of some random pastor; both are very false, as we’ll see.

The concept of Jewish Bolshevism, or “Judeo-Bolshevism,” was one of the most common antisemitic talking points of the last century, and remains the subject of immense misunderstandings on the modern far right. The narrative takes different forms. Most common has been the conspiratorial version whereby Bolshevism must be interpreted as a project of Jewish design with the goal of serving as a vessel for Jewish sadism and control over the gentile masses of the European East. I seek to clarify and correct some of the confusion on this subject with this article. In it, I address the attitudes toward Bolshevism among the Jewish masses, the Jewish share of the highest institutions of state and party over time, the conflicts between the actions of Bolshevism and the interests of the Jews, and the origins of much of the disinformation.

There are certainly important and relevant topics that have been excluded from the following for the sake of sticking to the purpose and simple feasibility. Among these, which I plan on addressing sometime in the future, are alleged Judeo-Bolshevik atrocities, namely events like the Holodomor, the Gulag system, and the Katyn massacre; the relationship between (Jewish) finance and the revolution/coup; and speculations about Stalin’s Jewish roots and affinities, a favorite topic among the spergs. Importantly, this is also not an article on Jewish activity in the Left generally, or even about Jews and the Russian revolutionary movement in particular, but specifically one about the Jews and the Bolsheviks after they took power.

Were the Jews Bolsheviks?

“When the October revolution came, the Jewish workers had remained totally passive, and a large part of them were even against the Revolution. The Revolution did not reach the Jewish street. Everything remained as before.” —Semyon Dimanstein, chairman of the Yevsektsiya

There are two ways to look at Jewish involvement in Bolshevism: with respect to the Bolsheviks and with respect to the Jews. Firstly, it’s undoubtedly true, as we’ll see, that among early Bolshevik elites Jews were substantially overrepresented. But it is also a generally accepted and demonstrable fact that the Bolsheviks were never popular among the Jews as a population, at least until the other options were taken out of the picture by force. In other words, there’s a marked disparity between the views of the average Jew, or the Jews of the region collectively, and that of select, individual Jews who managed to rise to the top of the Bolshevik ranks.

The views of the Jewish masses are best revealed in their voting patterns, which were demonstrated on a handful of occasions. Rabinovitch’s (2009) thorough analysis of Jewish votes in the elections held shortly after the February Revolution concludes that “Jews living in the territories of the former Russian Empire, when given the opportunity to participate in general elections, expressed only marginal support for the Jewish socialist parties and instead voted for parties and coalitions that principally demanded Jewish collective rights within a liberal framework.” This observation is made evident in the provided summary chart.

The same trend was seen in Jewish voting for the 1919 Polish legislative election, which “demonstrated the moderate social views of a basically conservative population much more interested in protecting its civil and national rights than in promoting social change” in the words of a relevant historian on the subject.

This status quo is also seen in the 1918 election of the Ukrainian Jewish National Assembly:

The first three parties [in the following chart], comprising over half the entire electorate, were outspokenly bourgeois, whereas the three at the end of the list were socialist parties but were extremely anti-Bolshevik; they received over a third of the vote. The Zeirei-Zion party was a people's socialist party, bridging, as it were, the Right and the moderate Left camps. (Nedava 1971, 154)

Popular support for Bolshevism came not from the Jews but primarily from the Russian proletariat of its large, industrial cities. Pipes (1994, 113) summarizes these facts well:

[W]hile not a few Communists were Jews, few Jews were Communists. When Russian Jewry had the opportunity to express its political preferences, as it did in 1917, it voted not for the Bolsheviks, but either for the Zionists or for parties of democratic socialism. The results of the elections to the Constituent Assembly indicate that Bolshevik support came not from the region of Jewish concentration, the old Pale of Settlement, but from the armed forces and the cities of Great Russia, which had hardly any Jews. The census of the Communist Party conducted in 1922 showed that only 959 Jewish members had joined before 1917.

In terms of rank-and-file membership in the CPSU itself, which was for most of its history seen as a privilege to obtain, Jews were consistently, though slightly, overrepresented with respect to their proportion of the Soviet population: “Representing just 1.8 percent of the total population in the 1926 census, Jews comprised 5.2 percent of party members in 1922 and 4.3 percent in 1927” (YIVO). To put things into context, the following chart compiles information on ethnic representation taken from the 1922 All-Russian party census.

Formatted from a tabulation in the Congressional

report “Conditions in Russia,” p. 86, also given

here in Russian and a number of other places.

While in 1922, 5.2% of the party was Jewish with respect to a population of around 2%, just 7.2 Jews per 1,000 were members. This becomes significant when one recognizes two facts:

(1) certain large populations like the Ukrainians (21.2% of the population based on that 1926 Census) were seriously underrepresented, which naturally increases the share of the other ethnic groups; and

(2) six other ethnic groups were more well-represented than were Jews, Latvians at an incredible 78 Bolsheviks per thousand and the Baltic peoples in general doing very well.

But this data comes even from 1922, or toward the conclusion of the Russian Civil War which saw an increase of support for the Bolsheviks and the Red Army among Jews. This was not an organic change of heart in the Jewish population. The White Army had worked to directly foster the myth this article is covering (this will be reviewed later), and the worst pogroms in the history of the region up til then were committed by White soldiers themselves culminating in perhaps 100,000 deaths. Bolshevik forces were not free from sporadic anti-Jewish excesses¹, to be sure, but by and large they stood opposed to antisemitic violence in rhetoric and action.

In terms of the genuine sentiments of the Jewish masses, however, it’s clear they were far more moderate and far less sympathetic to Bolshevism than is occasionally portrayed.

Were the Bolsheviks Jews ?

Overview

To avoid laymen’s confusion, we’ll need to briefly explicate the structure of the Soviet bureaucracy through Stalin. Although the Soviet Union was a one-party state, Lenin deliberately severed the party itself from governmental bodies. These structures were also frequently altered and replaced, so things can easily get tricky.

Starting with government: the USSR was, as the name spells out, a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, each having its government but with an overarching, preeminent Soviet government placed on top. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) was naturally most important among the subordinate republics. When one refers to the Russian or Soviet “government” of this era, what they typically mean is its Council of People’s Commissars (CPC, also called Sovnarkom): the commissars presiding over specific policy areas like agriculture or defense, along with the chairman, his deputies, and a couple other, minor positions. There was a CPC for the USSR along with one per each of the republics. (Before the USSR’s CPC was established in 1923, however, that of the RSFSR governed the entire state.) In 1946, the CPCs were replaced with Councils of Ministers (CM) which functioned similarly. The USSR’s CPC/CM had a chairman which served as its Premier, and which has also been referred to as the Soviet “Prime Minister.” The Congress of Soviets, formed in 1922, appointed these commissars/ministers, and was succeeded in 1936 by the Supreme Soviet. Both bodies were ultimately beholden to the decisions of the Communist Party per the doctrine of democratic centralism. The Congress of Soviets also elected a Central Executive Committee (not to be confused with the party’s Central Committee discussed later) which held most of the real power and acted between congresses. For the Supreme Soviet, this body was called the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. (Unusually, the CEC had multiple, simultaneous chairmen, but the Presidium had singular, successive chairmen.)

Regarding the party: The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) contained the most influential bodies of power. The party’s Congress was officially supposed to play the definitive role in Soviet affairs, electing Central Committee (CC) members to govern in between sessions (much like the government’s CEC), but it was ultimately beholden to whatever real leadership was in power at the time. The Congress convened typically every five years, but from 1939 through Stalin’s death, it was completely neglected. The CC housed major subdivisions: the Politburo (Political Bureau) was most important, and under Stalin basically preempted the CC itself; the Orgburo assigned members to various positions and oversaw the execution of party goals; the Secretariat was intended to perform technical, administrative work, but came to dictate day-to-day party activities, and its leader, the General Secretary, was also a member of the Politburo. “Candidate members” served advisory roles in these committees and were formally the pool of potential committee member replacements, but they had no voting rights by themselves.

Sources

A compilation of the members of the Bolshevik and RSDLP Central Committee, Politburo, Orgburo, Committee for Party Control, Central Inspection Commission, Commission for Soviet Control, and Central Control Commission, along with their ethnic backgrounds: http://holocaust.skeptik.net/misc/party.htm (https://archive.is/RIG8s)²

All Politburo members over time: Lists of members of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union - Wikipedia

An additional collection of links for the members of the sessions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party: The Central Committee of the CPSU

A Russian collection of the members of all the official bodies of the Communist Party and Soviet government, save the Council of People’s Commissars (says it’s under construction): knowbysight.info

A Russian collection of all the members of the Council of People’s Commissars over time, though compiled for each separate commissariat, as well as related bodies and organizations: http://2snk.site/

A now-offline list of the personal composition of all the governments of the RSFSR, in English (archived): elisanet.fi

A Russian collection of all the leaders of high-ranking bodies of power in the RSFSR, USSR, and Communist Party, though lacking their full personal composition: http://www.praviteli.org/records/

The annotated chart above³ gives some data I’ve compiled for the Jewishness of the Central Committee and Politburo in the period from the Politburo’s first convocation for the revolution all the way to Stalin’s death.

Of all the members of the Politburo from its formal establishment in 1919 to the end, there were four individual Jews (Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Kaganovich), along with four Georgians, 11 Ukrainians, and 89 Russians. If we go earlier to the de facto beginning at the sixth party Congress until January, 1919, there were 14 unique members, half of whom were Jewish (Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Sverdlov, Ioffe, Uritsky, Sokolnikov); and of the 26 total member slots for this period, half were also occupied by Jews. Of all the bodies of power, this earliest period of specifically the Communist Party saw the most extreme Jewish overrepresentation. In three brief periods, there was even a technical Jewish majority in the small Politburo compositions.

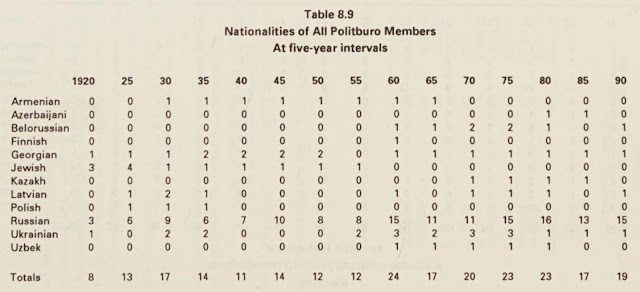

The 1992 book The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Politburo provides a useful chart of ethnic representation in the Politburo at five-year periods⁴:

Coming to terms with the Central Committee as body of political power to which even the Politburo was beholden, a few investigations have been carried out for this early period:

(1) Mawdsley (1995)⁵ examined the 78 full or candidate members of the CC from 1917–April, 1923, the “first generation of the Soviet elite,” and found that “[o]nly half (38/78) were Great Russian. The second largest ethnic group were the Jews, who numbered 13 (17 per cent). Eight more were Ukrainians, eight and five were from the minorities of the Baltic and the Transcaucasus respectively. Six further individuals belonged to as many different nationalities.”

(2) Riga’s (2008)⁶ analysis provides greater clarity on questions of ethnicity, analyzing CC members ostensibly from a slightly greater time period⁷ and finding roughly the same Jewish proportion as Mawdsley: 15%.

Mind you, both Mawdsley and Riga deal with unique members, while the available positions in the CC from year-to-year obviously frequently reused members. My chart displayed at the beginning of this section shows a consistently higher proportion of Jews in the CC from session to session (although never numerical dominance as with the Politburo), likely reflecting the fact that Jewish Bolsheviks tended to reappear at a greater rate than non-Jewish Bolsheviks, although the data also excludes candidate members unlike either Mawdsley or Riga. Either way, Jews apparently it’s clear that tended to be more successful in the Bolshevik apparatus, a generally expected phenomenon.

A handful of Jews including Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev remained among the most prominent Bolsheviks throughout the early period, although eventually they were famously purged by that notorious Georgian⁸, Joseph Stalin. The Jewish share of the Politburo diminishes greatly under the reign of Stalin, with the removal of all the Jews by the mid-20s until Kaganovich is installed in 1930. Jews become, in fact, underrepresented (~0.7% or six of 851 total post-Stalin elite in Mawdsley’s terms⁹) in the post-Stalin USSR where antisemitism becomes more pronounced and even official.

Government

Compared with the Communist Party, Jewish representation in the Russian and Soviet governments was much more modest. The following summary graph gives a timeline of the most important leadership positions of the USSR (left):

Of the 12 Premiers (leaders of the Soviet CPC/CM), none were Jews (0/12). (Wikipedia)

Of the 11 chairmen of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, Yuri Andropov¹⁰ was the only Jew (1/11). (Wikipedia) Regarding the earlier Soviet CEC chairmen, nine men held the role in overlapping terms; none of them were Jewish (0/9). (2snk.site)

Of the 11 General Secretaries (AKA Technical Secretary, Responsible Secretary, First Secretary) of the USSR, two were Jewish (2/11): Yakov Sverdlov (1918—1919) and Yuri Andropov (Nov. 1982—Feb. 1984). (Wikipedia)

For the RSFSR, of its 19 chairmen of the CPC/CM, none were Jews. (privateli.org) Of the 16 chairmen of the CEC/Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, the first two were Jewish: Lev Kamenev (Oct.—Nov. 1917), Yakov Sverdlov (—Mar. 1919). (privateli.org)

Of the government, Pinkus (1988, 81) writes¹¹:

On the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union (parallel to the Central Committee of the Communist Party) there were 60 Jews in 1927, 42 Latvians (from a relatively small population), 9 Germans and 7 Poles. That is to say, Jewish representation was low in comparison with the Latvians, but high in comparison with the other two nationalities, which were permanently under-represented in relation to their socio-economic weight. In 1929 the number of Jews on this body was 55, Russians 402, Ukrainians 95, Latvians 26, Poles 13, and Germans 12; so Jewish representation [9% of the total] declined slightly in comparison with the fourth Congress of the Soviets in 1927. In the 1937 elections, the first elections to be held after the ratification of the new Constitution of December 1936, 47 Jews were elected to the Supreme Soviet out of 1,143 delegates—that is, 4.1% of the delegates of both Houses—while their percentage of the whole population of the Soviet Union was less than 2%. So there was still Jewish over-representation in the highest representative institution of the Soviet Union.

Below we see the composition of the first Soviet government:

Similarly, in the first composition of the RSFSR CPC (again, which reigned supreme until the Soviet CPC was formed in 1923), Trotsky was the only Jewish commissar, People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs. According to Vedomosti: “In the government of the RSFSR from 1917–1922, Jews were 12% (six people out of 50).”

Secret Police

The Soviet security infrastructure was as convoluted and subject to change as anything else. The agency began as the RSFSR’s Cheka from 1917. In 1922 the Cheka becomes the GPU and is subsumed by the RSFSR’s NKVD (its internal affairs ministry). In 1923 the GPU becomes the OGPU and is now independent of the NKVD. In 1934 the OGPU becomes the GUGB and is subsumed by the USSR’s new NKVD. In 1943 the GUGB becomes the NKGB, independent of USSR’s NKVD. In 1946 the NKGB becomes the MGB. In 1953 the MGB becomes the MVD. In 1954 the MVD becomes the KGB, and things remain as such until the dissolution of the USSR (Wikipedia)

Statistics regarding Jewish participation in the internal affairs of these organizations are far more scattered and elusive than those for the previous subjects. Regardless, a decent understanding can be attained. Much of the following relies on Krichevsky's "Jews in the apparatus of the Cheka-OGPU in the 20s,”¹² digitally reproduced in parts one and two.

Under the notorious Cheka (1917–22) of the Pole, Felix Dzerzhinsky, only a very slight Jewish presence is detected along with a striking Latvian presence. In 1918, 4.3% of Cheka commissars (N = 70) were Jewish; 54.3%, however, were Latvian, a minority group comprising not 1% of the total. Jews comprised 8.6% of senior officials¹³ (N = 154) and 19.1% of investigators and deputy investigators (N = 42); Latvians 52.7% and 33.3%, respectively. Among the rank-and-file, of the approximately 50,000 members of the provincial Cheka offices, 9.1% were Jews, although this was naturally most pronounced in the former Pale of Settlement. Jewish, and generally national, representation was heterogeneous, and in this early period was highest among the investigators. It's possible to find certain tasks or subdivisions which involved greater Jewish (or Polish, or Russian, etc.) participation, but on the whole Jews were not all that salient.

Budnitskii (2012, 108–109) enumerates the Cheka leadership:

From 1917 to 1920 the membership of the upper echelons of the Cheka varied. In its first year (the Cheka was founded on December 7 (20), 1917), the Cheka appointed by the Sovnarkom included F. E. Dzerzhinsky (chair), G. K. Ordzhonikidze, Ia. Kh. Peters, I. K. Ksenofontov, D. G. Evseev, K. A. Peterson, V. K. Averin, N. A. Zhidelev, V. A. Trifonov, and V. N. Vasilevskii. By the very next day, only Dzerzhinsky, Peters, Ksenofontov, and Eseev remained. They were joined by V. V. Fomin, S. E. Shchukin, N. I. Ilin, and S. Chernov. By January 8, 1918, the collegium included Dzerzhinsky, Peters, Ksenofontov, Fomin, Shchukin, and V. R. Menzhinskii. They were joined by the leftist SRs V. A. Aleksandrovich (deputy chair, though he was later replaced by G. D. Zaks, who had by then joined the Bolsheviks), V. D. Volkov, M. F. Emelianov, and P. F. Sidorov. After the elimination of the leftist SRs and their removal from positions of power, the membership roll included Peters (who ran the Cheka for a period until the investigation of the leftist SRs was completed), Dzerzhinsky, Peters, Fomin, I. N. Polukarov, V. V. Kamenshchikov, Ksenofontov, M. I. Latsis, A. Puzyrev, I. Iu. Pulianovskii, V. P. Ianushevskii, and Varvara Iakovleva, the sole woman to serve in the Collegium of the Cheka during the Civil War period. They were later joined by N. A. Skrypnik and M. S. Kedrov. In March 1919, a new collegium was announced, which included Dzerzhinsky, Peters, Ksenofontov, Fomin, Latsis, Kedrov, Avanesov, S. G. Uralov, A. V. Eiduk, F. D. Medved, N. A. Zhukov, G. S. Moroz, K. M. Valobuev, and I. D. Chugurin. By 1920 the collegium consisted of Dzerzhinsky, Ksenofontov, Latsis, N. I. Zimin, V. S. Kornev, Menzhinskii, Kedrov, Avanesov, S. A. Messing, Peters, Medved, V. N. Mantsev, and G. G. Yagoda. Thus, from 1918 to 1920, four Jews served in the highest governing body of the Cheka: Zaks, Messing, Moroz (who first headed the Instructional Section, and later headed the Investigation Section), and Yagoda, who would work in the Cheka from 1920 onwards. [Bold added]

In the rebranded OGPU of 1923, 15.7% of the leadership (N = 96) was Jewish. An increasing proportion of Jews developed as the agency began to require education more extensively, Jews being a better-educated demographic: “14 out of 15 Jews in the leadership of the OGPU apparatus had a secondary and higher education (93%), among the Poles this figure was 8 out of 10 (80%), among Russians, 28 out of 54 (52%), among Latvians, 3 out of 12 (25%).” Latvians (12.5%), while still more overrepresented than Jews, were on their way out of the organization as the fervor of the Civil War had waned. In 1924, the Central Office (N = 2,402) was 8.49% Jewish and 8.66% Latvian. The district department heads in 1927 (N = 36) were 14.7% Jewish and 10.8% Latvian. In the same year, leading employees (N = 34) were endowed with “Orders of the Red Banner in connection with the 10th anniversary of the Cheka”; of this group, Jews were 23.5%, Latvians 8.8%. The Problem Gene’s original research¹⁴ into the ethnic composition of the later (1929) OGPU leadership alleges 22% was Jewish, 11% Latvian, and 5% Polish. This is consistent with a general elevation of the Jewish proportion of Soviet secret police leaders to a high point at the very end of the OGPU, with Jews standing at 39% of high-level officials, seen below.

The ethnic composition of secret police leadership¹⁵ from 1934–1941 is covered by Russian historians N.V. Petrov and K.V. Skorkin as part of broader research.

Taken from here.

1934 is when the OGPU ends and is replaced by the GUGB of the newly-created NKVD of the USSR. The Jewish Genrikh Yadoga remains at head until 1936, replaced by the Russo-Lithuanian Nikolai Yezhov. The high point of Jewish participation in the leadership of Soviet secret police occurs in the mid-1930s. When Yezhov takes over, he purges a great deal of Yagoda’s staff, and the proportion begins to fall. When the Georgian Lavrentiy Beria usurps him two years after that, the Jewish share plummets to just a couple percentage points. It never recovers. Petrov and Skorkin cover the purges of 1938–39 here, and note that many “foreign nationalities” — Jews, Latvians, Poles, Germans — take a hit, with Georgians and Ukrainians as exceptions.

Was Bolshevism in Jewish Interests?

According to Judeo-Bolshevik doctrine, the USSR was a mechanism for Jewish supremacy and control, i.e., for advancing specifically Jewish interests. How did this play out in reality? The following is a review of just some of the ways in which Soviet policy contradicted Jewish interests.

(1) Of all national groups, Jews had the highest proportion of those classified lishentsy (“deprived”) at 23.6%–39.1% (Kimerling 1982, 44). Most lishenets were deemed exploiters of the workers — merchants, clergymen, those who earn income from capital rather than labor, many employers, prior Imperial officers, the mentally disabled. Once classified, you were unable to vote, be elected, receive higher education or training, obtain socialized health care or housing, etc., until you complete five years of industrial or agricultural labor. This classification applied until 1936.

(2) The Bolshevik party line regarded Jews as, unlike Latvians, Russians, Poles, etc., not actually a nationality but an aberrant identity only kept in existence by capitalism. During the days of the RSDLP, Lenin frequently clashed with the Jewish Bund as it began to demand increasing autonomy and national rights for Jewish workers. In his notes on the Jewish Question, he deals extensively with the Bundists, likening their demands for a Jewish school system to Southern segregation and self-imposed medieval ghettoization (p. 9), and summing up with “Whoever directly or otherwise puts forward the slogan of Jewish national culture (however well intentioned he may be) is the enemy of the proletariat, the defender of the old and caste element in Jewry, the tool of the rabbis and of the bourgeoisie” (p. 13). Stalin was even more direct, writing in Marxism and the National Question: “The question of national autonomy for the Russian Jews consequently assumes a somewhat curious character: autonomy is being proposed for a nation whose future is denied [i.e., will inevitably assimilate away] and whose existence has still to be proved!”

(3) It goes without saying that the early USSR fiercely opposed Zionism in addition to traditional Jewish life, viewing both as reactionary and counterrevolutionary; however, this was also the program of the Jewish Bund. Pipes (1993, 366) relates: “In September 1919, the Evsektsii shut down the Zionist Central Office and the following year got the Cheka to arrest and exile numerous Zionists. In 1922, the campaign resumed with arrests and trials in Russian and Ukrainian cities. In September 1924, police raids resulted in the detention of several thousand Zionist activists.” The Evsektsii, or Yevsektsiya, was a Jewish section of the CPSU tasked with bringing communism to the Jewish masses in addition to crushing rival ideologies.

(4) Contrary to frequent portrayals, Jewish religion was not free from persecution in the slightest. What’s true is that the Russian Orthodox Church was the main focus of the anti-religious campaigns, as it was by far the largest force to be reckoned with. But Jews, Catholics, and Muslims were likewise not safe from the destruction. (You can clearly see that all religions were included in Soviet policies regarding their practice.) Early on, the teaching of Hebrew, which coincided as both a language of Jewish religion and of Zionist revival, was banned, rendering the training of rabbis and Jewish students officially impossible. In 1921, all Jewish religious schools were closed. For a time after, general anti-religious policy was relaxed; when it intensified again in 1927 through the 30s, the preeminent Lubavitch Rebbe Yosef Schneersohn was arrested and expelled and the Moscow and Leningrad synagogues were closed. In Leningrad, three synagogues remained in 1932, compared with two dozen in 1917 and despite its Jewish population population quadrupling from 1917–1939 (YIVO).

The ruins of this synagogue of Vitebsk can be viewed on Google Maps here. (Vitebsk - jguidetoeurope.org) Image taken from A Century of Ambivalence, p. 117.

The synagogue on the left was a Karaite Jewish kenesa in Simferopol, Ukraine closed in the ‘30s. Notice the Soviet star at the top, which replaced a former star of David. The other two are a kindergarten and movie theater, built over the Great Synagogue of Vilna and Czernowitz Synagogue, respectively—both closed by the Soviets.

Also published at the Mischling Review

The ruins of this synagogue of Vitebsk can be viewed on Google Maps here. (Vitebsk - jguidetoeurope.org) Image taken from A Century of Ambivalence, p. 117.

The synagogue on the left was a Karaite Jewish kenesa in Simferopol, Ukraine closed in the ‘30s. Notice the Soviet star at the top, which replaced a former star of David. The other two are a kindergarten and movie theater, built over the Great Synagogue of Vilna and Czernowitz Synagogue, respectively—both closed by the Soviets.

(5) The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939–1941) between the Nazis and the USSR saw extensive cooperation between the two. Consequences of the Pact included financial cooperation, the partition of Poland, and the providing of Germany with a crucial Soviet naval base. Before the agreement, foreign Communists dismissed the rumors, but after it was signed they almost uniformly dropped their anti-Nazi agitating and instead lobbied the other way. For example, the American Peace Mobilization formed in the place of the anti-fascist American League for Peace and Democracy in order to push for a Lindbergh-like “peace” with the Nazis, condemning the Lend-Lease program and FDR. Then, upon Operation Barbarossa, it reverted once more.

(6) Despite post hoc Communist propaganda, there was no Soviet policy for the evacuation of the Jewish population of Eastern Poland to save them from the Nazis. This was true even at the outbreak of Operation Barbarossa, and the great majority of Jews remained in Poland only to perish in the Holocaust. “[T]he largest group of Jews rescued from the annexed territories were those who were deported before the outbreak of the war” (Pinchuk 1980). Said deportation of Poles to labor camps in Siberia was in many cases lethal (Illinois.edu). Jews were highly disproportionate among the deportees, with 30% of all deportees during this period being Jewish and 25–30% perishing in the process (Mendes 2014, 22–3).

(7) The USSR didn’t teach the Jewish Holocaust in its school system and rarely publicized it, instead emphasizing the losses of ethnic Russians. Contrast this with the West which, so the story goes, is dominated by Jewish influence and accordingly Holocaust propaganda abounds, although this too wasn’t the case until arguably the 1970s (iwm.at, Poltorak and Leshchiner 2000, CSMonitor).

(8) The Socialist Reich Party was a post-War neo-Nazi party set up in West Germany by ex-SS Otto Ernst Remer. Until it was abolished in 1952, it expressed very positive views of the USSR, which in turn financed its operations for a time, electing the same destabilization policy of the KPD before WWII. In an interview obtained by the IHR, Remer remarked that “Stalin not only had millions killed who were on the periphery of power, such as peasants, but he also had 1.6 million of Lenin's followers, including Trotsky, systematically shot as well. And as a result, Russia today is regarded as the only country that is anti-Jewish or free of Zionist influence. We Germans ought to be glad for the rivalry between Washington and Moscow. We have to take advantage of these differences.” (JHR Archive)

(9) In the 1950s, propaganda campaigns propagating a Zionist infiltration narrative were held and show trials highlighting alleged Jewish anti-Soviet conspiracy were staged: e.g., the Slánsky Trial, the Doctors’ Plot.

(10) Despite the narratives of the Judeo-Bolshevism theorists, the Soviet relationship with Israel also undermines notions of Jewish hegemony, or Jewish control over Stalin as is occasionally alleged.

After WWII, the Soviets moved to consolidate their power for the coming Cold War with the United States. Initially, this included supporting the establishment of the state of Israel. The Soviet Bloc voted to admit Israel as a US membership in a 37/58 vote. During the 1948 war and the British supplying Arab troops, the Soviets in turn supplied Israelis with Czechoslovakian arms. The reason for this was twofold: 1. Israeli independence would oust Britain as the region’s dominant power, and 2. Israel was an anticipated socialist ally. Conspiracy theorists must ignore these Soviet interests and later Soviet antagonisms and instead dwell on this brief period of support, in isolation.

Israel attempted to appease both the US and USSR. Nonetheless, the USSR refused to let any of its Jews emigrate even in the wake of the Holocaust and Israeli wishes; starting in 1948, a wave of arrests of Jewish leaders and closures of Yiddish schools began in the new policy of Russification as an attempt to forcibly keep Russian Jews loyal to the regime. At the close of the Independence War and after full UN recognition, Israel no longer needed Soviet support and postured toward the US, accepting a major loan and voting for US interests in the UN, including regarding the Korean War. With point one accomplished and point two clearly lost, the Soviets no longer had reason to support Israel. About a month before Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet legation in Tel Aviv was bombed, and while Israel condemned the action the USSR cut off all diplomatic ties. Ever since, it sided with the Arab states, in 1955 supplying Egypt with weapons as it had Israel (Gyoo-hyoung 1998).

The War of Attrition in the late 60s saw actual Soviet troops fighting alongside the Arabs, at least 58 of whom were killed. Operation Rimon 20 was an Israeli-Soviet dogfight intended to put an end to Soviet meddling.

(11) In the Post-Stalin USSR, anti-Zionist imagery proliferated and took on an obviously antisemitic look; see examples here. Another striking example is the Soviet work Judaism without Embellishment, an attempt at atheistic and anti-Zionist propaganda which attacked the Jewish religion as a unique evil, claimed Jews had aided the Nazis in their invasion of the Soviet Union, and relied on blatantly antisemitic imagery. The work otherwise did concede that there are “righteous Jews” who turn their backs on Zionism and Judaism. The full book can be viewed here, though I do not believe an English translation is available.

About the Disinformation

So then what accounts for all the disinformation on this topic? It’s very common to see lists of almost entirely Jewish names purporting to be authentic compositions of the Soviet government, for example; where does this come from?

For the most part, they come from the contemporary journalist Robert Wilton. Wilton was re-popularized by IHR director Mark Weber, who republished his The Last Days of the Romanovs with addenda including Wilton’s compiled lists of Bolshevik leaders and their ethnicities, which Wilton provided “[i]n order not to leave myself open to any accusation of prejudice,” amusingly enough.

All one needs to do is compare this information to that given earlier to realize that Wilton essentially made everything up. But he had reason to…

In “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia's Early Soviet Regime,” Weber describes the book as “one of the most accurate and complete accounts of the murder of Russia’s imperial family.” Fortunately, he even cites his claims:

On Wilton and his career in Russia, see: Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), pp. 141-142, 144-146, 151-152, 159, 162, 169, and, Anthony Summers and Tom Mangold, The File on the Tsar (New York: Harper and Row, 1976), pp. 102-104, 176.

I only managed to find Summers’ and Mangold’s The File on the Tsar online, but it actually references the other book as well. In spite of Weber’s opinions, from the very pages he cites, both show a consensus on Wilton and his supposed accuracy:

In other words, Wilton’s scribblings are nothing but White Army propaganda. While perhaps not crafting the myth in its entirety, the Whites were responsible for propagating and disseminating the notion that Bolshevism and Judaism were one and the same, exemplifying how antisemitism can be a perfect instrument of propaganda. The Bolsheviks weren’t opponents in an ideological struggle but just the disguise of an archetypal enemy already familiar to the Russian or Ukrainian peasantry.¹⁶ In this sense, much of the anxiety about Judeo-Bolshevism was “artificial.”

But there were other reasons, including an already fairly popular association between Jews and the Left. (The reasons for this association, to the extent it existed, will be dealt with in a later article.) In the context of the former Russian Empire, this was especially significant, since the Jews who were previously barred from imperial offices now made up many of the early Soviet leaders. And Jews were also particularly visible, being generally more literate and verbally capable than others, which must have amplified their perception past what the facts could technically warrant.

Conclusions

The Communist takeover in Russia saw an influx of minorities, largely from intellectual backgrounds and the professions, into positions of leadership. Riga’s (2008) analysis found that two-thirds of the early Bolshevik elite belonged to an ethnic minority background. Of the ethnic groups, Jews usually were not the most numerous nor even the most overrepresented, but nonetheless were enough of each to make a considerable impact on the revolution and early institutions of power.

But in what way is this relevant?

Was Bolshevism “a project of Jewish design with the goal of serving as a vessel for Jewish sadism and control over the gentile masses of the European East”? If it was, it wasn’t very good at it. Throwing Jews into labor camps and out of the Politburo and NKVD do not seem to align very well with the Judeo-Bolshevik understanding of events. But that much should be clear. (This blog isn’t necessarily written for paranoid schizophrenics, anyway, and this article is intended to aggregate and contextualize some important facts for rational people interested in the subject at hand.)

But Jews actually comprised a majority of the Politburo at a few, brief, early periods in its existence. Why does this matter? Of what practical significance is it to any serious person? If one’s being equally unserious, he could point out that the first de facto Politburo of August 1917 and the first de jure Politburo of 1919 were minority-Jewish, and the October 1917 Politburo was operational only for a few days to direct a coup that was actually opposed by Jewish Bolsheviks. Regardless, this prominence was not a lasting feature, and the fact it fades so quickly in just the first decade of Bolshevik rule shows that Jewish power and Jewish consciousness in this institution were minimal, regardless of the number of Bolsheviks who may have technically come from Jewish backgrounds. I will not get into the level of ethnic consciousness among these figures in this article (see my next response to MacDonald), but suffice it to say it was typically minimal and did not inform their revolutionary impulses. By the time of WWII, when Nazi partisans were propagandizing the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism the hardest, Jewish participation in the party and state was far from “dominant.”

If not dominance or control, then does the notable overrepresentation of Jewish Bolsheviks matter in some practical way? One wonders why, if this were true, the peddlers of these notions would rely so heavily on laughably inflated statistics from obviously unreliable sources. Or why there’s zero focus on the Latvian (or perhaps Georgian) role in the Bolshevik regime, give how abundant they were in the party and especially Cheka. You’d have no trouble at all compiling a few cheesy graphics of Latvio-Bolshevik faces, since apparently that kind of thing is enough for some.

Some will instead take up the argument of collective guilt: the very fact that (ethnic) Jews were involved so much with Bolshevism (and leftism in general) means that it’s on their descendants as a community to denounce them and atone for their sins, or something.

Arguably first made by VV Shulgin in What We Do Not Like Them For, and described in good detail in The Jewish Century (pp. 180–188), E. Michael Jones also puts it forth in The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit¹⁷:

If Jews can disclaim responsibility for communism by claiming that Trotsky wasn't a "real Jew," can't the Germans do the same thing, by disowning Hitler? Hitler, after all, had been born in Austria, not Germany. Couldn't the Germans just as easily say, "these weren't real Germans, they were just the scum."

This is the message EMJ repeats throughout his chapter on Bolshevism. Put in reverse, it might be assumed he believes that the entire German people deserves blame for the actions of Hitler and the Nazis.

Either way is just bad logic and ethics: individual Germans don’t deserve blame for the Nazis just as much as individual Jews don’t deserve blame for Jewish Bolsheviks. If individuals are to incur blame based on their own actions, collective guilt as a concept makes no sense. This is also one of those moments where people who make the argument forget how frequently it’s applied to their own group. Surely they wouldn’t agree that “the whites” of today are responsible for slavery or various genocides and atrocities committed by their (potential) ancestors?

But, of course, there’s also a big detail EMJ leaves out. The important, relevant, and obvious difference between Trotsky and Hitler is that the former didn’t identify as with his Jewishness and, more importantly, was not inspired to act on its basis, whereas Hitler and the Nazis very passionately identified as Germans — in fact, that was kind of their raison d’être. The latter tried to represent the German people and also involved a good majority of the contemporary German populace; the former didn’t do either. This is the premise for why some Jews will renounce Trotsky as “not really Jewish,” and in all fairness they’re right.

___________________________

Additional Notes

(1) “[T]he Red Army was responsible for 8.6 per cent of the Civil War pogroms” (McGeever 2019, 4).

(2) Note: Dmitry Manuilsky, a Ukrainian, is wrongly identified as Jewish. Otherwise, the list is accurate.

(3) I used multiple sources to corroborate information. The Skeptik.net list gave basic ethnic information, but it was incomplete. There were many members listed without an ethnic identifier (71 of the 125 given for the XIX Congress, for example), so I had to search around the Web to find those whom I could confidently identify as Jewish or non-Jewish, which was a good majority. (Searching the Russian Web with the Cyrillic names yields much more information.)

(4) The book also clarifies important things about the nature of the early Politburo. The year 1919 marks the point where the “history begins” for the institution. Before then, inner circles of the Central Committee had been set up since 1908, but have “not always been recognized as the precursor to the all-powerful Politburo” (9). The first nominal convocation of October, 1917, for example, never formally convened past when it was assembled on the recommendation of Felix Dzerzhinsky, and there’s “no evidence that the Bureau worked during the Bolshevik seizure of power two weeks after its establishment” (8).

(5) Mawdsley’s findings are also included in a 2000 book he cowrote: The Soviet Elite from Lenin to Gorbachev.

(6) Riga’s findings are also included in a 2012 book she wrote: The Bolsheviks and the Russian Empire.

(7) Mawdsley (N = 78) restricts his analysis up to April of 1923, intentionally excluding “an enlarged Central Committee was elected at the 12th party congress in that month.” It appears Riga (N = 93) includes the full year 1923.

(8) Or, apparently, that notorious Ossetian, at least in part, as pointed out in the comments of this piece by Homo heidelbergensis.

(9) See Mawdsley’s book mentioned in note 5: p. 109, footnote 42.

(10) Andropov was half-Jewish but apparently lacked any Jewish identity (Wikipedia).

(11) Professor Benjamin Pinkus surveys Jewish involvement in Soviet institutions on pages 76–83 of his 1988 book The Jews of the Soviet Union.

(12) This source is a standard for investigations into this topic, being used in works like The Jewish Century and Russian Jews between the Reds and the Whites. The reproduction is in the Russian original, so make good use of a browser translate extension. Most of the relevant statistics are taken from the included charts.

(13) Defined as “heads and secretaries of departments, commissioners, investigators and their deputies, instructors, etc.”

(14) “Jews In The Soviet Secret Police” @ 5:50

(15) Definitions are important: “In the study, we took into account the people's commissars of internal affairs of the USSR and their deputies, heads of departments and departments of the central apparatus of the NKVD, people's commissars of internal affairs of all union and autonomous republics (the exception was the Nakhichevan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic), heads of the UNKVD of the territories and regions that were part of the RSFSR, the Ukrainian SSR, the Byelorussian SSR and the Kazakh SSR. The heads of the NKVD of those autonomous regions of the RSFSR that did not change their administrative status during the period under review, as well as the heads of the NKVD of the regions within the Kirghiz, Tajik, Turkmen and Uzbek SSRs, were not taken into account. At the same time, the heads of the NKVD of those autonomous regions of the RSFSR whose status has been upgraded to autonomous republics have been taken into account by us. The total number of leaders of the NKVD from July 1934 to February 1941 was constantly growing as a result of the formation of new administrative-territorial units, as well as changes in the structure of the central apparatus of the NKVD, the emergence of new departments and departments. The number of employees of the NKVD of the considered level almost doubled - from 96 to 182. Especially intensive growth was observed in 1938–1939, which was primarily due to the expansion of the structure of the central apparatus of the NKVD.”

(16) For more on this, see chapter five of Russian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917–1920.

(17) This book has a horribly misinformed chapter on Bolshevism which I plan on reviewing when I find the time.

Also published at the Mischling Review

No comments:

Post a Comment

All Comments MUST include a name (either real or sock). Also don't give us an easy excuse to ignore your brilliant comment by using "shitposty" language.